Modern war is no longer limited to battlefields alone; He is increasingly intrusion into the daily life of civilians. The deliberate targeting of non-combatants marks one of the most serious violations of international law, undergoing both humanitarian principles and the world’s world-based order.

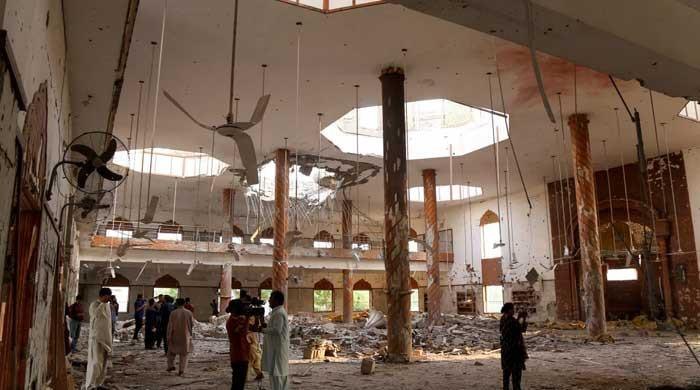

In May 2025, India’s operation, Sindoor, precisely inflicted such a violation. By hitting houses, mosques, markets and essential services, the operation resulted in at least 40 civilians in Pakistan and Azad Jammu and Cashmire.

These deaths were not accessories or guaranteed, but rather the foreseeable result of strikes in spaces where no military objective was present.

The consequences of these actions extend far beyond the immediate losses of life. They erode the credibility of the world order based on rules, normalize impunity and define a dangerous precedent in which humanitarian protections are considered optional rather than compulsory.

At a time when conflicts extend through land, air, cyber and information, the erosion of humanitarian principles threatens to redraw the limits of acceptable wartime in a deeply destructive way.

From a legal point of view, the case against Operation Sindoor is clear. Article 2, paragraph 4, of the Charter of the United Nations prohibits the use of force against the sovereignty of another State, while article 51 authorizes self -defense only in the case of an armed attack. By invoking article 51 to justify its strikes, India has abused international law. Terrorism, as serious, does not constitute an armed attack justifying the interstate military aggression only if the participation of the State can not be established in a credible manner.

In the case of the Pahalgam incident, no credible evidence has been presented connecting Pakistan to events. Instead, a tragedy on Indian soil was used as a pretext for cross -border strikes, violating the letter and the spirit of international law.

Geneva conventions offer even clearer prohibitions. Articles 15, 27 and 32–34, as well as the common article 3, explicitly protect civilians against targeting, tortured or collectively. The strikes of Operation Sindoor in civil districts and religious sites fell downright in the prohibited field of conduct.

The international community cannot afford to deal with such violations such as current characteristics of conflicts. This would make the protections enshrined in humanitarian law without meaning, reducing them to ambitious ideals rather than enforceable obligations.

The moral issues are also austere. When civilians – women who are looking for water, children at stake and families in prayer – become deliberate targets, war ceases to fight between the armies and rather becomes a campaign against humanity itself.

The standardization of this practice has serious implications for global security. It triggers a cycle of reprisals, radicalization and perpetual instability, while also undergoing the credibility of states that claim to maintain human rights.

The wider geopolitical context also requires a meticulous examination. The Sindoor operation is not alone; It is part of a wider model of policies that marginalize and dehumanize Muslim populations in South Asia.

The parallels with other conflict theaters, in particular Israel’s operations in Palestine, are difficult to ignore. In both cases, civilians are dehumanized by being labeled as “terrorists” or “collateral damage”, a rhetorical turn of the hand that masks the systematic violations of humanitarian law.

The erosion of standards in a conflict invariably pours into others, weakening the global architecture of responsibility.

The lessons for Pakistan are urgent. First, there is a need for systematic legal preparation. The allocation and documentation are the constituent elements of responsibility.

Without evidence, photographs, testimonies and medico-legal files, allegations of civil civilian risk are rejected as a political rhetoric. Legal audits, structured files and independent surveys must form the backbone of Pakistan during international forums.

Institutions such as the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court may not guarantee rapid justice, but they provide platforms to establish a legal file that can influence global opinion and politics.

This emergency was resumed during a recent seminar organized by the Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad (ISSI) on “Civil Protection in Multidal Conflicts: Legal and Humanitarian Prospects on Operation Sindoor”.

Ambassador Sohail Mahmood, the director general of the ISSI, underlined the need for Pakistan to build stronger diplomatic coalitions to highlight these violations during multilateral forums.

In his final remarks, Mr. Ahmer Bilal SOOFI, former Minister of Law and Justice, stressed the importance of structured legal documentation and preparation so that Pakistan can effectively pursue responsibility under international humanitarian law.

Second, Pakistan must recalibrate its diplomatic strategy. The dependence on bilateralism with India has failed to hand over several times. Multilateral platforms – UN, the organization of Islamic cooperation and even regional groups – offer more viable paths to amplify the concerns of Pakistan.

Diplomatic awareness must connect the Sindoor operation with the broader continuum of the Human Rights file from India to cashmere, its treatment of minorities and its use of water as a coercive tool. Construction of states coalitions around these problems can generate momentum where unilateral protests cannot.

Third, the narrative construction is central. International law operates not only before the courts but also before the Court of public opinion. Histories of victims, displaced families, orphaned children and destroyed communities have a moral weight that statistics cannot transmit alone.

Social media platforms, international media and civil society organizations are essential to transform legal arguments into convincing stories that resonate worldwide. Without this, the human dimension of these tragedies may be drowned by the noise of geopolitics.

Finally, Pakistan must strengthen its own internal resilience. Civil protection is a question of national cohesion, not just law and diplomacy. Divided societies are less able to defend their citizens abroad. Stronger social unity, economic resilience and institutional capacity are essential to ensure that external advocacy is equal by internal stability.

A country perceived as fractured and unstable will find it difficult to obtain sympathy for its victims, whatever their cause.

The Sindoor operation raises questions that go beyond the immediate tragedy of May 2025. It asks if the international community is ready to maintain the humanitarian principles which it so often invokes. He asks if powerful states will be held to the same standards as the weakest, or if the selective application will continue to dig the legitimacy of international law.

Above all, he asks if civilians in conflict zones can ever expect the protections promised to them by treaties and conventions.

For Pakistan, the way to go is clear. Legal appeal, diplomatic awareness and narrative construction must operate in tandem. None of these tools alone can guarantee responsibility, but together, they can question impunity and preserve the principle that civilians must never be the target of war. The Sindoor operation was an attack on the idea that war has limits.

Allowing such an act to pass without dispute would invite rehearsal, not only in South Asia, but also wherever powerful states choose to fold the rules.

Civil protection must therefore remain at the heart of the foreign policy and the national security strategy of Pakistan.

It is not only a legal but also moral imperative. To defend civilians is to defend the very principle of the humanity of war. The Sindoor operation has tested this principle. The answer must reaffirm it, with clarity and conviction, before the erosion of humanitarian standards became irreversible.

Warning: The points of view expressed in this play are the own writers and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of PK Press Club.TV.

The writer is an expert in public policy and directs the Partner Institute of the World Economic Forum in Pakistan. He publishes @amirjahangir and can be reached: [email protected]

Originally published in the news