High Court to hear rare petition seeking disqualification of sitting judge, reopening debate over judicial immunity

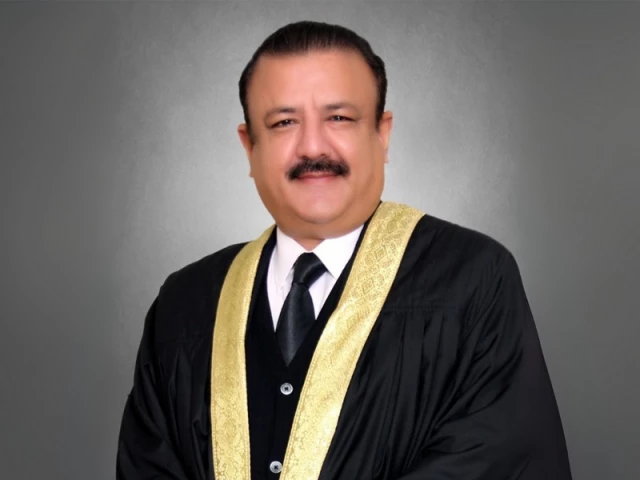

Judge Tariq Mehmood Jahangiri. Photo courtesy: IHC

ISLAMABAD:

A legal tool once widely used to oust lawmakers has now entered much more sensitive territory, as the Islamabad High Court (IHC) prepares to hear a quo warranto petition challenging the eligibility of a sitting high court judge, a development that has reignited the debate over judicial immunity and constitutional guarantees.

A division bench of the IHC, headed by Chief Justice Muhammad Sarfraz Dogar, is expected today (Monday) to consider a petition seeking disqualification of Justice Tariq Jahangiri on the grounds that he holds an invalid degree.

This case marks a rare moment in Pakistan’s legal history where the jurisdiction of quo warranto, traditionally exercised against elected representatives and executive office holders, is put to the test against a member of the higher judiciary.

These proceedings come against the backdrop of a long and contested history of judicial activism following the reinstatement of judges in March 2009, when quo warranto was repeatedly invoked to impeach lawmakers, prime ministers, heads of accountability institutions and civil servants.

Senior lawyers argue that these interventions weakened Parliament, a trend that is now being reexamined as the same jurisdiction turns inward.

According to Article 225 of the Constitution, no election dispute can be challenged except through an election petition. However, the Supreme Court has disqualified many legislators by exercising quo warranto jurisdiction under Article 184(3).

Since the Lawyers’ Movement of 2007, different Chief Justices of Pakistan (CJP) have adopted various approaches to judicial activism.

Top lawyers agree that exercising quo warranto against lawmakers in the past has weakened Parliament, with the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) becoming the main victims. However, the situation has now changed following the adoption of the 27th constitutional amendment.

According to legal observers, the executive now enjoys greater dominance over the judiciary. They say even judges who are not in the government’s good graces face pressure from their own ranks.

Last week, the quo warranto petition against Justice Jahangiri was declared maintainable, following which the IHC issued notice to its own judge for today (Monday).

Judge Jahangiri himself is expected to appear in court.

Advocate Zafarullah, who is acting as amicus curiae in the case, supported the contentions of petitioner Mian Daud, saying that the eligibility for appointment of a High Court judge could be ascertained through a quo warranto order and could not be examined under Section 209 before the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC).

He, however, clarified that a writ of quo warranto and a writ of habeas corpus were maintainable against a judge of a high court, while writs of mandamus, certiorari or prohibition were not maintainable against a judge of a high court.

On the other hand, a section of lawyers raised strong objections to maintaining a quo warranto petition against a judge, arguing that if such practice were to commence, Article 209 of the Constitution would become redundant.

A lawyer pointed out that the constitutional requirement for a High Court judge is a license with ten years of legal practice under Article 193 of the Constitution. Although a diploma is required to obtain a license, it falls under the jurisdiction of the bar councils.

Recently, the SC ruled that a judge of the same court cannot issue any summons or file any action against another judge of the same court.

“The constitutional system of immunity for superior court judges is intended to ensure the independence of the judiciary, which is the commandment of Article 2A of the Constitution.”

“It is for this reason that a judge of the same court cannot issue any summons or bring any action against another judge of the same court.” “Reliance in this sense is placed on the case of Muhammad Ikram Chaudhry,” said a detailed 11-page judgment written by Justice Jamal Khan Mandokhail while hearing a contempt case against SC Additional Judicial Registrar Nazar Abbas for his failure to dispose of a matter in court in violation of court orders.

The order said that in pursuance of discharge of constitutional functions, clause (5) of Article 199 of the Constitution grants immunity to judges of the SC and high courts for acts done in their judicial and administrative capacity.

“The analogy to immunity is to prevent a judge of a court from abusing his jurisdiction and authority by judging and controlling another judge of the same court.

“It protects the judge against any interference from outside or within the institution. It safeguards the integrity and authority of the court and strengthens the ability of judges to exercise their functions without problem, ensuring that their decisions are not influenced by the fear of being subjected to adverse measures.” “The concept of immunity aims to preserve the authority of the judicial institution, which is crucial for the rule of law and the proper administration of justice. »

The court further observed that if a judge of a superior court cannot issue a summons to another judge of the same court, then a judge cannot have the power to issue directions or initiate proceedings under Article 204(2) of the Constitution against a sitting judge of the same court and punish him for contempt of court.

“Allegations of misconduct against a judge of the Supreme Court or a high court can only be investigated and dealt with under Article 209 of the Constitution by the Supreme Judicial Council (SJC),” the order said.