When the ruling elites are no longer willing to commit to constitutional values, we can no longer guarantee the dignified life constitutionally promised by Jinnah’s Pakistan.

The impact of the 26th and 27th Amendments led to the resignation of two Supreme Court judges and a judge of the Lahore High Court, who protested against the erosion of protection of fundamental rights of citizens, which has effectively disfigured the social contract between citizens and the state. Resignation letters are most instructive when read as part of a broader critique of government policy and the justice system itself. A public debate is necessary to reverse a trend that has left the state and society drifting institutionally and normatively. But what brought us to this sad situation?

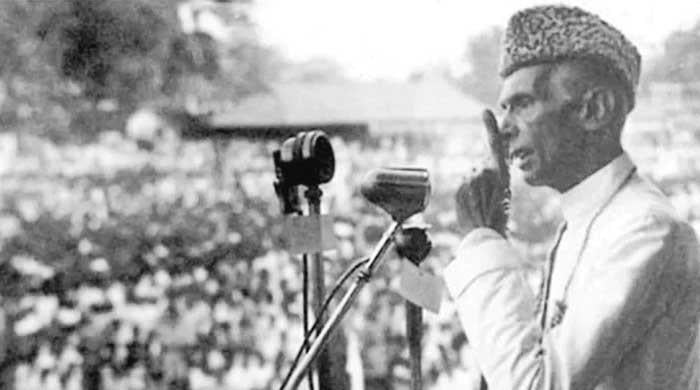

Although we continue to revere Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah as the founder and great leader of Pakistan, we have conveniently left aside a vital aspect of his thought: his conception of Pakistan as a moral or dignified state, with defining characteristics such as the rule of law, fairness, freedom of conscience and representative democracy.

Jinnah’s speeches and letters outline the founding narrative and include ideals that address various aspects of statecraft, governance, and foreign policy. Instead of being a ‘living’ source of inspiration, the Quaid has been relegated to history with the salutary portrait hanging in our hallowed corridors of power and living rooms.

What defines a dignified or moral state are the generally accepted moral standards and aspirations to which society and the state are committed, and which are usually contained in the constitution. On this, Jinnah maintained: “Islam and its idealism taught us democracy. He taught the equality of man, justice and fair play.”

The judiciary played a vital role in institutionalizing the separation between Pakistan as a mere fact and the state as a moral entity. In KB Ali v. State (1975), the Supreme Court rejected “standards of reason or morality” as defining valid law. Although it is fundamental to ensuring social cohesion, ensuring good governance and guaranteeing a dignified life for all, it considers that valid law is whatever is ordered by “a competent legislator”. After granting almost unlimited powers to the legislative and executive branches, it has been very difficult for the judiciary to control governance within the framework of constitutional constraints.

Such judicial reasoning reduced Jinnah to a historical figure whose task was accomplished by the administrative and legal recognition of a formal state – a historical fact. In doing so, we have effectively removed Jinnah’s moral ideals from state practices, policy and legal thinking.

Although the judiciary is constitutionally charged with protecting and interpreting constitutional norms and values, it has now diverted the course of the state towards secular, power-based government.

Not only has this jurisprudence eroded the moral basis of policy, legislation and interpretation, but it has also predisposed Pakistan towards authoritarianism. An “empowered” legislative and executive branch have encroached in various ways on the independence of the judiciary. The result: a grotesque depiction of elite interests and power politics that exposes the state as it has become: an oligarchy.

Against a backdrop of judicial divide (under the 26th Amendment) and weak democratic standards, the recent amendments were adopted without rigorous public scrutiny and consensus on their intended moral and strategic benefits. According to the ICJ, “it is alarming [that] a constitutional amendment of great importance and public interest was adopted in a very secret manner and in less than 24 hours.”

The amendments were also adopted while setting aside the founding narrative and two substantive criteria that protect the moral content of the Constitution. One that laws inconsistent with or in derogation of fundamental rights shall be void (Article 8) and secondly, no law shall be enacted which is contrary to the injunctions of Islam (Article 227).

Our rule of law is therefore a clever mix of secular and Islamic protections, which has not been developed in jurisprudence, nor applied by the judiciary to test and illuminate the design and quality of constitutional order and governance.

Islamic scholar Mufti Taqi Usmani criticized the 27th Amendment, insisting that absolute or lifetime immunity from prosecution for any person is a violation of Islam and the Constitution (Article 25). The International Commission of Jurists has criticized both the 26th Amendment as a “blow to judicial independence” and the 27th Amendment as a “blatant attack on the independence of the judiciary and the rule of law.”

Wider implications on the main features of the constitution and system of governance also need to be examined through the doctrine of the basic structure (of the constitution). In the 2015 Supreme Court case, District Bar Association Rawalpindi v. Federation of Pakistan, Justice Sheikh Azmat Saeed said: “[A]So long as the amendment has the effect of correcting or improving the constitution and not of repealing or abrogating the constitution or any salient part of it or of substantially modifying it, it cannot be questioned.”

It can be argued that with the reconfiguration of judicial appointments, reduction of powers of judicial review, transfers and postings, creation of a new superior court and related measures, the salient features have been significantly altered and warrant rigorous scrutiny.

While Jinnah insisted on justice and complete impartiality as a “guiding principle”, Pakistan ranked 129th (out of 142) in the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index 2024, reflecting further erosion of an impartial rule of law that guarantees equality for all (Article 25).

Commenting on the 26th Amendment, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) noted the “extraordinary political influence” and observed that “they [the amendments] erode the ability of the judiciary to function independently and effectively to check the excesses of other branches of state and protect human rights.”

Referring to the 27th Amendment, the ICJ observed: “They will significantly harm the ability of the judiciary to hold the executive to account and protect the fundamental human rights of the people of Pakistan.” The change in the balance of power must be constitutionally justified.

This entire unfortunate saga of constitutional amendments betrays the intellectual and moral bankruptcy of our institutions of governance – the civil and military bureaucracies and the judiciary. Although Jinnah insists that caring for the poor is our “sacred duty,” public welfare is a lesser consideration: constitutional social and economic rights, set out in the Principles of Policy, are not even enforceable by the courts.

Instead of a constitutional amendment to make rights such as fundamental rights directly enforceable, the 26th and 27th Amendments arguably erode what little constitutional governance we had. What is lost in this Faustian bargain is public welfare and dignity – Jinnah’s Pakistan.

A superficial appreciation of the Constitution has hollowed out the normative meaning of the institutions of state and society.

Our institutions, intellectuals and constitutionalists have failed to elaborate and stick to the founding narrative of Jinnah and “[t]“the great ideals of human progress, social justice, equality and fraternity” to inform policy and legislation, guide future generations and ensure that we remain focused on the original mission.

Not only is it a disservice to the ordinary Pakistani who holds Jinnah’s promise dear, but it is also a disservice to Jinnah by not appreciating it in a proper intellectual and moral context.

Consequently, and arguably, we are witnessing the resurgence of an executive state that Jinnah fought fiercely against for much of his life. We need new, clear jurisprudence to ensure a morally worthy state. Without rediscovering Jinnah intellectually and morally, we will never realize Jinnah’s Pakistan. Who can Pakistani citizens trust now?

The writer is a former secretary of the Law and Justice Commission of Pakistan.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of PK Press Club.tv.

Originally published in The News