My journey with Case #9 crossed continents: the United States, the United Arab Emirates and Pakistan. Accustomed to a diet of romantic comedies, starry romance and vampires, my mother was skeptical when my sister insisted we watch the series.

The very first episode was horrible as Seher was raped at her boss Kamran’s house. A disturbing watch with heartbreaking visuals that burst off the screen. Nevertheless, my mother, my sister, my sister-in-law and I, our group of four, were fascinated by the drama that drew us into the world of Seher who sets out to seek justice.

Seher’s journey stretches from a devastated rape victim trembling in the courtroom before the rich, powerful and entitled Kamran to a courageous survivor who looked her rapist in the eyes and left him squirming. Words matter – at first, Seher saw himself as a victim. Her brother goes so far as to imprison her at home, her mother only caring about what people will say.

But once Seher decides to speak out, she becomes a survivor who stands tall. Author of After Silence: Rape and My Journey Home, Nancy Raine says, “Words seemed to make it visible. But speaking, even when it embarrassed me, also slowly freed me from the shame I felt. The more difficult I found it to speak, the less power the rape and its aftermath seemed to have over me.”

In Pakistan, rape victims are often tormented by society. A woman from Degwal, Sargodha, who was gang-raped by servants of the landlord, committed suicide by setting herself on fire due to the taunts of the women of the village. His suicide note read: “They told me I was injured and should never be allowed to walk the village streets again. They said I had dishonored my family. I wanted to end my family’s misery as well as my own. They said if I had any respect for myself, I should kill myself out of shame.”

Rape is the only crime where the survivor is cast in the role of the attacker and subjected to a battery of questions: the victim’s blame is endless and soul-destroying: What were you wearing? Why did you come out so late? What did you do? It is precisely this type of pervasive regressive mentality that Case 9 sensitively addresses. The drama tackles sexual assault, institutional apathy and the emotional toll of legal battles.

While the justice system is full of unscrupulous lawyers and police officers, as Case 9 shows, it is rare to have an honest judge who delivers a historic judgment. Compare this with the behavior of Additional District and Sessions Judge Nizar Ali Khawaja on March 25, 2009 in Karachi. The judge asked Kainat Soomro, a 15-year-old gang rape survivor, to describe her rape in front of the accused who allegedly threatened and bribed Somroo’s family to settle out of court.

In front of 80 spectators, the defense lawyer and the judge asked a series of invasive questions about the rape. He was asked when certain clothes were removed, what exact actions were inflicted on him and when. When Kainat replied that she did not remember because she had passed out, the judge reprimanded her. This is what rape victims face when they take their rapists to court.

Recent judgments by Justices Mansoor Ali Shah and Ayesha Malik call for an end to gender stereotypes against rape survivors and a focus on this crime. Justice Malik linked rape cases to the constitutional rights to life and dignity. These judgments are reflected in laws such as the Anti-Rape Investigation and Trial Act of 2021, which aim to create a fair legal framework for rape survivors.

Despite these progressive laws, in reality, rape survivors and their families face problems due to misogynistic mindsets and institutional apathy. Case 9 sets a precedent for courtroom etiquette and how rape cases should be handled at the earliest stages of police report and medical examination. Legal challenges, filing of FIR, vital importance of preservation of evidence, engagement of lawyers, court proceedings and recent changes in the law were highlighted.

Small nuances dot the series; for example, when the principled SP leaves his room to take action against Kamran for raping Seher, the camera focuses on the SP’s wife kissing and holding their young daughter close to her. No words are spoken. Then there is Ali Rehman Khan as Seher’s ex-husband who supports her all the way and hopes to revive their relationship. Seher kindly tells him to go and live his life. Seher is her own hero and she doesn’t need a messiah.

Case 9 showcases the power of female camaraderie and the empowered women who support Seher: her lawyer Beenish, her friend Manisha, her best friend in Canada, and Kamran’s wife Kiran, who ultimately provided the crucial piece of evidence. Even though men have a brother code, it is refreshing to see women coming together and moving mountains with their dedication and conviction.

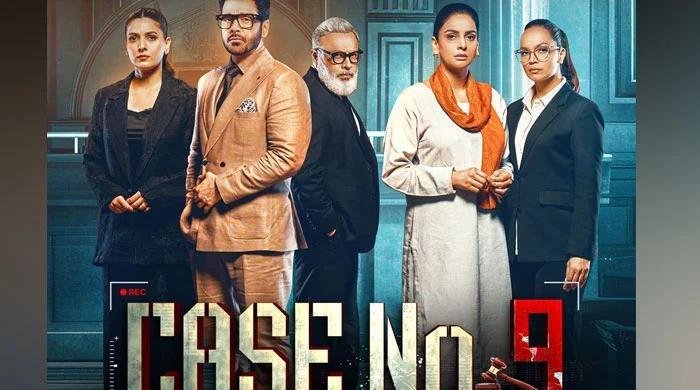

The legendary Saba Qamar, Faysal Qureshi, Amina Sheikh and Gohar Rasheed lived their roles, but the revelation was the excellence of the supporting cast. A tense and sensitive screenplay by Shahzeb Khanzada stands out, without irritating filler elements; each actor played a vital role in the progression of the story. Naveen Waqar and Junaid Khan were superb as Kamran’s friends Manisha and Rohan, as was Rushna Khan as Kamran’s wife Kiran: all three faced moral dilemmas which they overcame.

An interesting technique was the insertion of the Shahzeb Khanzada show in the series where Seher and Kamran compete against each other. Building on the credibility of the show, it lent authenticity to the facts as well as the alarming statistics and graphs on rape and sexual assault highlighted by Shahzeb. “When a woman says no, she means no” and “Raise your boys better” were two key messages from him.

Our group of four watched Case 9 in deep silence: tea was sipped quietly, phones were muted, children were silent. After each episode, there were serious conversations about what we had just seen on screen. My mother and many of my friends said they learned a lot from Case #9 and that they are not the only ones. The impact of this series will go a long way in disrupting the conspiracy of silence and misogynistic mentality surrounding sexual assault that has been prevalent in Pakistan for far too long.

The writer is an author, journalist and change agent. She can be reached at: [email protected]

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policies of PK Press Club.tv.

Originally published in The News