Slough, England:

Those of you who are thirsty for a quick and easily digestible thriller that breaks at the speed of light and overflows with conspiracy theories that bend in mind are advised to give a very wide place to the British successful show of Netflix, to make Netflix, British, Success, Success, Adolescence.

If, on the other hand, you rather like to be immobilized on the sofa with your heart torn, looking at the wall long after the credits rolled up in oblivion, Adolescence is your cup of tea. Although we must warn you at this stage that it is unlikely that cups of tea be. All the hot drinks that you may have prepared with love will be left cold on the arm of your sofa when you are caught in the horror of what is happening when we let teenagers have unhindered access to social media.

Divided into four -hour episodes and written by Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham, Adolescence is the kick at the back of all the parents before they are about to give up proposals led by the child who imply the words “Instagram” and “but the parents of everyone …”

The balance of probabilities stipulates that all boys with a social media account will not corrode in an uncertain, disgusting and hateful bruising psychopath Adolescence Jamie Miller. But as Adolescence Takes pain to illustrate, to embark on the radioactive experience which gives a child a child and an antibut helmet is likely to stick a damp finger in a living socket just to see what is happening. Should we really try fate and allow our sons to venture into a digital cocoon dominated by the tastes of Andrew Tate’s Manosphere? Unless you are itself reading this, it is unlikely that you need the reply.

A fly on the wall

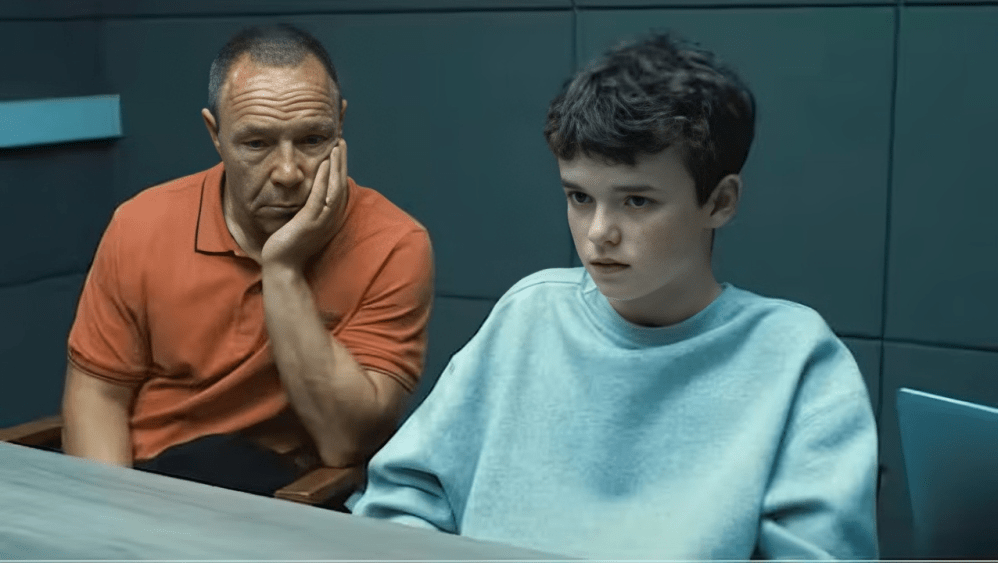

We open with the police who beat a suburban family as they stop their thirteen years, Jamie (played perfection by Owen Cooper, fifteen, in his very first role), suspected of the murder of a classmate.

The word “suspicion” is used very freely here, because Jamie was carefree enough to make his stab induced by rabies in a parking lot in view of a well -placed video surveillance camera. Whatever opening full of action, thriller lovers to believe, there are no deep plots waiting. Despite Jamie’s weak protests on the contrary – like a child who insists that they have not eaten this cupcake despite the chocolate frosting cheeks – we are very quickly about to discover that there is almost no doubt about Jamie’s guilt. It is not a whodunnit. It is not even a HowDunnit. This is a whydunnit.

Director Philip Barantini has chosen to shoot Adolescence In a transparent socket. Although this means that it is very difficult to obtain all aspects of the consequences of the murder – for example, we do not have time to pay tribute to the family of the murder victim – it is the closest that you will have ever been a fly on the wall in a murder investigation. (A slight caution: if you are currently fighting against a headache, keep yourself watching this show until the pain relievers have been launched. The camera never rests, never, and you will be forced to hold a pack of ice heads if you continue recklessly in your debility.)

With this camera on the movement, we then follow Jamie in the police station as he read his rights and attribute a lawyer, the boy choosing his father (played by the impeccable Stephen Graham) to act as his adult appropriate ”. We drag the camera into the room where Jamie’s parents and the older sister are held, clinging to the fervent belief that their son could not have played a role in this infernal nightmare. Their raw horror is scribbled in sight, and you can almost believe that you are looking at a documentary instead of a scripted show. The use of a soundtrack is maintained at the smallest of the minimums. Almost against our wills, we are pulled in the same fresh hell as Jamie’s family, and we cannot look away. Before the end of the episode, we – with Jamie’s father, Eddie and his lawyer – are faced with overwhelming evidence that no one can deny. Anxiety not filtered for loss of innocence and the son whom he will never find thefts on Eddie’s face while he collapses in a sorrow of sorrow.

A haunting lesson

Throughout the four episodes, one thing obviously lacks: the victim of the murder, Katie’s, the family. As Barantini discovered it, when you turn with a camera to a work in the wall, you do not have the luxury of time to explore each tentacle of a crime like that of Jamie. But it is not the story of Katie, nor that of the haunted and shredded emptiness of that of her family.

No, this is Jamie’s story. More specifically, it is the story of the way in which the minds of young boys are molded because they are exposed online to pornography and male ideals, and left poorly equipped for neither empathy of the port, nor to face the rejection. As Margaret Atwood so strongly observed it in a collection of tests, men are afraid that women make fun of it, and women are afraid that men kill them. It is the knot of Jamie’s motive: at the end of the day, he could not bear that a girl he was pursuing could make fun of him.

There are no deep and dark secrets that hide in the shadow of Jamie’s family life. There is no alcoholic mother, no absent father, no drug abuse under the surface in the currents. Jamie is the product of a happy and loving family, the only crime of which was to give him a smartphone and say yes when he asked for a computer in his room. While we – with his psychologist – discover, before submitting to his murderous impulses in the face of rejection, Jamie spent many nights swallowed by the instructor and locked himself up in his digital world, his headphones sealing the outside world. Where children once had the works of JK Rowling and Rick Riordan to keep them company before sleeping, boys like Jamie spend their nights bombed with subliminal toxic masculinity messages on social networks.

The destruction of Jamie’s crime leaves in his wake does not concern anyone – especially his family. More than a year later, we see the sorrow anchor them as they try to sail in life with the haunting knowledge that they are not impeccable. Even if they want to admit, Jamie’s parents accept that their practical approach to gadgets has played a hand in the murderer without remors that their son has become. Jamie is the villain, but falling prey as he did with male ideals, he is also a victim. While his father, Eddie, sobbed in Jamie’s plush with the wish that he could have done better, too, we succumb to tears. Because we know that when our boys succumb to invisible pressures, the border between us and Eddie is thin.

Do you have something to add to the story? Share it in the comments below.