Lahore:

At the Child Protection Office of Lahore, the sound of laughter rings in the corridors where young children spend their days studying, playing and dreaming of the future.

Among them is Mahwish Aslam, 17, a teenager with a soft voice trying to remain optimistic but in calm moments, she admits to feel deeply anxious. In a few months, Mahwish will be 18 years old and will say goodbye to the refuge because she will be legally adult. Without family, without house, and without a clear idea of what comes then, the sudden transition to adulthood haunts many young girls living in the office.

Ramsha Aamir and Nasreen Maqbool, who share a living space with Mahwish at the refuge, echo the similar fears that are the two awake at night, wondering what life would look outside the refuge.

When the refuge provides them with food, education and a safe place to sleep, their future is uncertain when they cross the legal threshold of adulthood since the Bureau of Child Protection and Protection operates under the legal laws of child protection which only support the age of 18. In other words, once a child becomes a legal adult, they are supposed to leave the age of 18. In other words. A transition that is far from smooth.

In the absence of transition centers for dedicated young people, there is no formal mechanism to ensure that young people reaching adulthood are able to find safe accommodation, continue their studies or obtain a job.

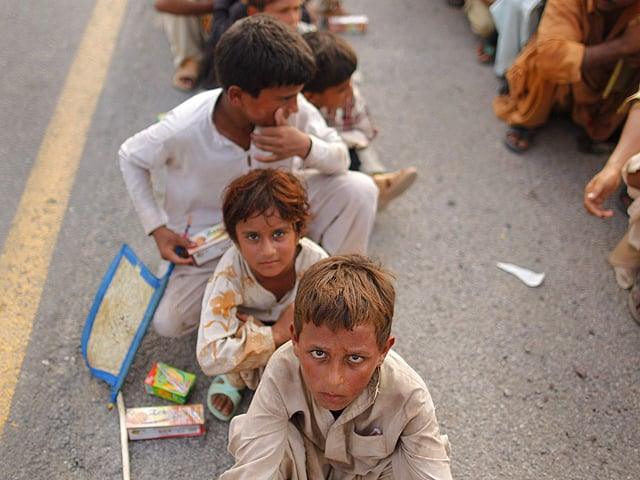

Consequently, for most abandoned children, the steep end of institutional support resembles a cliff without safety net below. Without life skills, social networks and economic means to survive independently, many young adults can fall into homelessness, informal work or abusive situations.

Iftikhar Mubarak, director of Search for Justice, thought that this gap in the child protection system was not only a political defect, it was humanitarian surveillance. “While the law classifies these children as adults after the age of 18, these young people are still emotionally and economically who need support. Although there have been stories of success, they remain the exception, not the rule,” said Mubarak.

Muhammad Zubair and Nazia Ashraf, who both grew up in the refuge, have formed a link during their years of care. With the support of the office, they got married, found jobs within the same institution and began to build a family life together. Others, such as Hassan, Sanwal and Mubarak Aslam, have been able to obtain vocational training and are now employed in private companies. A small number of private organizations, such as the SOS children’s village, provide prolonged care for young people beyond the age of 18.

According to director Almas Butt, SOS allows residents to stay until the age of 23. “During this period, young adults receive support for placement, career advice and emotional advice. The boys are generally transferred to youngsters for young people, while girls stay in the village until they are married or financially self -sufficient,” said Butt.

These efforts, although impactful, are limited in scale and capacity, because most shelters and social protection programs simply do not have the resources or mandates to offer similar services. In the absence of public policy, these few private institutions have become lines of life for those who have had the chance to access it.

In countries like the United Kingdom, Canada and South Africa, structured programs guide young people during their first years for adults with hostel housing, financial support, skills training and psychological advice.