The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine to prevent cervical cancer will be deployed from September 15 in the Sindh, health officials warning that community distrust, persistent rumors and gaps in the training of vaccinators could undermine the campaign.

About 50% of the target group is registered in schools, with current coordination [between health officials and the] Department of Education to facilitate vaccinations at school, said Dr. Rehan Baloch, speaking during the Globe HPV seminar at Aga Khan Uniferisty (AKU).

“We have assigned about 200 million rupees for the HPV vaccine, with additional GAVI support and other partners to advocate and awareness,” he said, stressing the need for a stronger commitment with parents, teachers and health care providers.

The campaign will be based on pediatricians, gynecologists and front -line workers to inform communities about the prevention of HPV and cervical cancer.

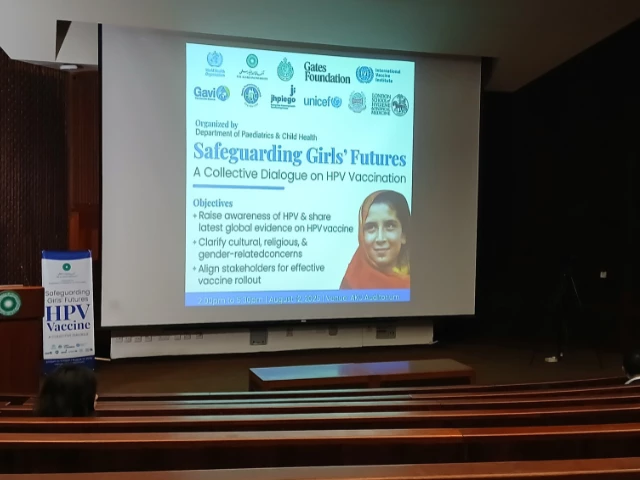

PHOTO GAPESSITY: AKU

The SINDH has expanded the Immunization Project Program (EPI), Dr. Raj Kumar, described deployment as a “historic initiative” and that preparations were focused on operational logistics and microplanning at the level of the Union council, based on the experience of the campaigns of measles, typhoid and polio.

Officials said 20 million girls aged nine at 14 are registered in the country’s schools, the rest outside the school. It is estimated that 70% of vaccinations will take place in schools and others will be administered in community areas thanks to partnerships with public and private sectors.

What is HPV?

Cervical cancer kills more than 300,000 women worldwide each year, with the heaviest dead number in low and average income countries. In Pakistan, the disease is among the main cancers in women and is often diagnosed too late, although it is largely avoidable by vaccination in a timely manner.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) – A sexually transmitted infection – is responsible for 91% of cervical cancers worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 291 million women are diagnosed each year and around 340,000 die from the disease, most of them in countries like Pakistan.

Recent estimates indicate that each year in Pakistan, 5,008 women receive a diagnosis of cervical cancer and 3 197 die from the disease, according to the human papillomavirus and related cancers, information sheet 2023.

The HPV has more than 200 known types, classified into low -risk and high -risk categories. While most low-risk infections are asymptomatic and resolve themselves, high-risk HPV 16 and 18 strains are linked to 70 to 80% of cervical cancer. In Pakistan, nine out of 10 cases are caused by these two strains. The country reports around 5,000 new cases and 3,000 deaths each year, with 73 to 74 million women in danger.

The HPV vaccine is the most effective for girls from nine to 14 years old, but coverage is hampered by data gaps, slow deployment and social barriers. The standardized impact rate by the age of Pakistan is 6.1 per 100,000 women – above the threshold recommended by the WHO of four or less. The global WHO 2020 strategy provides for vaccine 90% of girls in this age group by 2030, but global adoption remains less than 15% due to delays in national programs.

The Zekolin vaccine introduces to Pakistan protects against the types of HPV 16 and 18, which, according to the modeling of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (CIR), could prevent up to 83% of cases of cervical cancer in Asia in the Mediterranean, the Central, the West and the South of the East. More recent vaccines covering several types of HPV may increase 95%protection.

Commitment descending approach led by the community

The success of the HPV campaign in the Sindh will depend not only on logistics but also on the fight against deep social inequalities. A technical and descending approach risks alienating communities already excluded from decision -making, emphasizing the need for participatory strategies that deal with local populations as equal partners in health initiatives.

Pakistan health and education inequalities in Pakistan cannot be resolved by technical fixes alone, warned Dr. Kausar S Khan, a human rights researcher, calling for participatory action research and community engagement as the basis of social policy.

The country’s policy and the academic elite – researchers, bureaucrats and superior service providers – form a privileged small minority, while “the poor, women, minorities, transgender people and those who have different sexual orientations” constitute the majority but remain excluded from decision -making, stressed by Dr. Khan.

“In Karachi, more than 50% of the population lives in Kachhi Abadis without water, electricity or sanitation-and yet we want to bring them science,” she said, warning that an approach from high down heavy in science ignores participative ethics and local realities.

Inspired by his work in research on participatory action, Dr. Khan urged a “approach based on power and strength -based” which begins by “knowing each other” and the treatment of communities as equal partners rather than passive beneficiaries of awareness campaigns by focusing on vaccination initiatives by the HPV of the Department of Development of Women. This, she said, is lacking in the campaign.

However, the hypothesis that vaccines and other technical interventions can solve deeply rooted social problems is incorrect.

“The successes we see are technical. But the social side is where it was,” she said, stressing that performance indicators and programmatic processes cannot replace real inclusion of the community.

Gaps and awareness

Awareness of cervical cancer and human papillomavirus (HPV) in Pakistan remains alarming, with rooted cultural norms and a gender dynamic posing major challenges to the absorption of the VPH vaccine, according to the social and behavioral team of JPEGOS CAHPS presented by the Social and Behavioral Team of UNICEF (SBC).

The study revealed that only 17.2% of respondents were aware of cervical cancer, that 4.4% of caregivers had heard of HPV and only 2.9% knew the existence of the HPV vaccine. UNICEF officials have said that fear of cancer could be a motivator, but false ideas about hygiene, fatalistic beliefs and the limited role of women in the decision -making of health seriously hampering acceptance.

Language and framing has proven to influence perceptions – the “vaccine” spoke of the hope and the prevention of adolescent girls, while “injection” sparked fear of needles and disease. UNICEF co-creation sessions have focused on the representation of girls as ambitious subjects rather than vulnerable objects, and using images that reflect real communities instead of idealized versions.

Awareness of the HPV vaccine is particularly low, 95% of those questioned have never heard of it. However, confidence in official councils is high – 90% said they would accept the vaccine if they were recommended by the government, a doctor or religious leaders. About 76 to 81% expressed their interest in cervical cancer or HPV screening, and 79 to 80% said they would vaccine themselves or their daughters.

Obstacles include access to vaccines, family objections, minor fears concerning pain or side effects, cost problems and embarrassment due to false ideas on the need for the vaccine. The reluctance is significantly higher in mothers than girls.

Mothers have emerged as the key keys to consent, due to their close communication with girls, while fathers – often not involved in daily health decisions – hold passive approval that can block campaigns.

“In fact, mothers who have shown greater knowledge of cervical cancer have shown a [bigger] Risk of not wanting to vaccinate their daughters in relation to those who had never heard of it, “said Dr. Fyezah Jehan, professor and president in Aku.” It is confidence and comfort, and responding to these concerns, which will allow us to better manage it. “”

She added that acceptance is the highest when mothers include both the benefits and security of the vaccine, without having general concerns about infantile immunization.

Social listening efforts of UNICEF and other partners are underway to identify local concerns and adapt communication strategies to strengthen the confidence of vaccines and prevent hesitation. The results indicate that parents and health workers require targeted commitment.

“We must convince our vaccinators, our health workers even more than this vaccine is good, then they will transmit this confidence … communities and the main stakeholders,” said Dr. Paul Bloem, who has the main technical manager of the HPV vaccine, stressing the need for continuous training to strengthen confidence.

Despite solid safety data, rumors persist, in particular statements connecting the infertility vaccine. The World Vaccine Safety Committee has repeatedly examined such allegations and has found “no association between HPV and infertility vaccination”. Experts note that the vaccine can actually help prevent infections that can reduce fertility.

The evidence of other countries, such as Bangladesh, show that meticulous preparation and the adoption of a strategy in one dose can reach national coverage rates above 90% during the launch. Managers warn that without similar bases in Pakistan, a high coverage from the start – critical for long -term success – will remain out of reach.