Kharo Chan: The crusts of salt cracks under the foot while Habibullah Khatti heads towards the grave of his mother to say a last farewell before abandoning his island village of the strings on the Delta of the Indus.

The intrusion of seawater in the Delta, where the Industry River meets the Oman Sea in the south of the country, triggered the collapse of agricultural communities and fishermen.

“Saline water surrounded us on the four sides,” said Khatti AFP from the village of Abdullah Mirbahar in the city of Kharo Chan, about 15 kilometers (9 miles) from the place where the river is chewed in the sea.

While fish stocks fell, the 54 -year -old man turned to seam until it also becomes impossible, with only four of the remaining 150 households. “In the evening, a strange silence takes over the region,” he said, while stray dogs wandered through the wooden and bamboo houses.

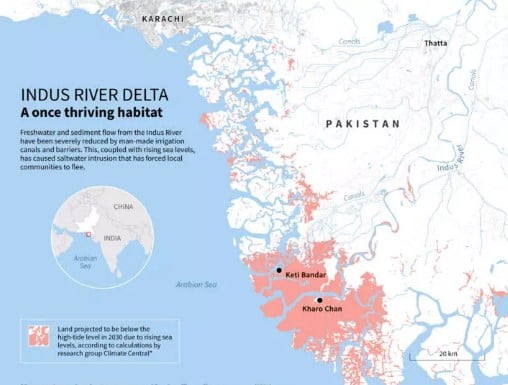

Kharo Chan included a 40 villages, but most of them disappeared under the rise in sea water. The city’s population increased from 26,000 in 1981 to 11,000 in 2023, according to census data.

Khatti is preparing to move his family to Karachi, nearby, the largest city in Pakistan and swelling with economic migrants, including the Indus Delta.

Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum, which defends fishermen’s communities, estimates that tens of thousands of people have been moved from coastal districts of the Delta.

The abandoned houses are represented in one of the villages in the city of Kharo Chan, in the Inda delta on June 25, 2025. – AFP

However, more than 1.2 million people have been moved from the Global Indta region in the past two decades, according to a study published in March by the Jinnah Institute, a reflection group led by a former Minister of Climate Change.

The downstream flow of water in the Delta has decreased by 80% since the 1950s due to irrigation channels, hydroelectric dams and climate change impacts on the melting of glacial and snow, according to a 2018 study by the American Center-Pakistan for advanced water studies.

This led to a devastating intrusion of seawater.

The salinity of water has increased by around 70% since 1990, which makes it impossible to cultivate crops and seriously affect populations of shrimp and crab.

“The delta flows and shrinks,” said Muhammad Ali Anjum, a local WWF ecologist.

Swallowed by increasing water level

From Tibet, the Industry river crosses the cashmere before crossing the entire length of Pakistan. The river and its tributaries irrigate approximately 80% of the country’s agricultural land, supporting millions of livelihoods.

The delta, formed by rich sediments deposited by the river when it meets the sea, was once ideal for agriculture, fishing, mangroves and fauna.

But more than 16% of fertile land has become unproductive due to the encroachment of Seawater, a study by the Government Water Agency in 2019 revealed.

In the city of Keti Bandar, which is spreading inside the water on the water, a white layer of salt crystals covers the ground. The boats transport drinking water to miles away and the villagers return it home via donkeys.

“Who willingly leave their homeland?” said Haji Karam Jat, whose house was swallowed by the rise in the water level.

He has rebuilt later in the land, providing that more families would join him.

“A person only leaves his homeland when he has no other choice,” he said AFP.

Loss of land, culture

British colonial leaders were the first to modify the course of the Industry river with canals and dams, more recently followed by dozens of hydroelectric projects. Earlier this year, several channel projects on the industrial river were interrupted when farmers in the low river regions of the Sindh province protested.

To combat the degradation of the Industry river basin, the government and the United Nations launched “the initiative of the living industrial” in 2021. An intervention focuses on the restoration of the delta by attacking the salinity of the soil and protecting agriculture and local ecosystems.

The Sindh government is currently directing its own mangroves restoration project, aimed at relaunching forests that serve as a natural barrier against the intrusion of salt water.

Even if mangroves are restored in certain parts of the coast, land grabbing and residential development projects lead to compensation in other regions.

Neighboring India poses an imminent threat to the river and its delta, after having revoked a 1960 water treaty with Pakistan which divides control of rivers from the Indus basin.

He threatened not to reintegrate the treaty and build dams upstream, hugging the water flow to Pakistan, which described it as a “act of war”.

In addition to their homes, the communities have lost a lifestyle closely linked to the Delta, said climate activist Fatima Majeed, who works with the Pakistan Fisherfolk forum.

Women, in particular, who for generations have sewn the nets and wrapped up the catches of the day, find it difficult to find work when they migrate to the cities, said Majeed, whose grandfather has moved Kharo Chan’s family to the periphery of Karachi.

“We haven’t just lost our land, we have lost our culture,” he said.