The Thornewood Inn in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, was once the quintessential New England bed and breakfast, with its comfortable four-poster beds and wraparound porch, attracting tourists from Boston, New York and beyond.

But these days, many of the Thornewood’s rooms are filled not with peepers or antique hunters, but with the people who serve them.

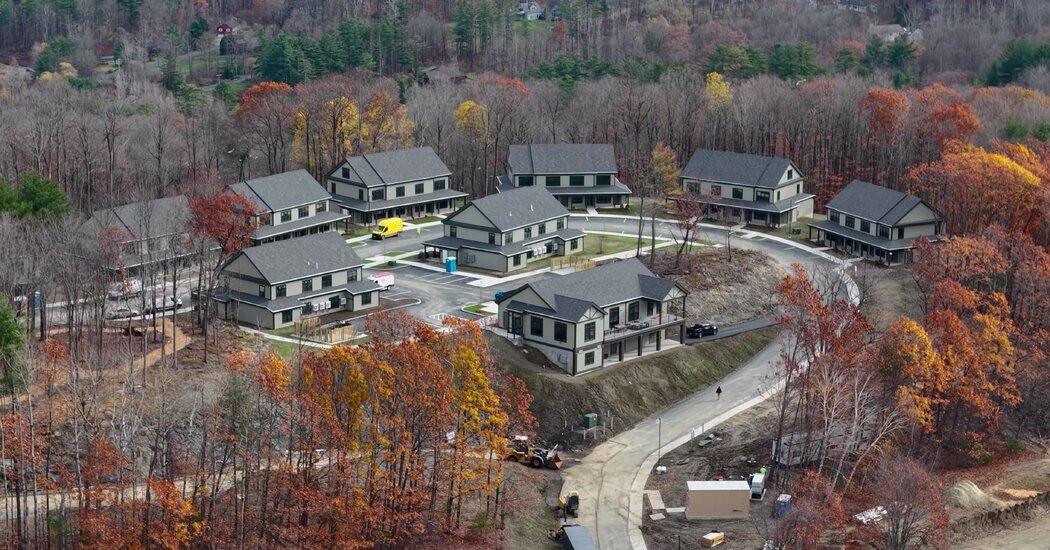

They’re people like Adam Figueiredo, 32, who worked at a coffee shop in town when he was looking for a place to live this summer. After months of not finding anything he could afford, Mr. Figueiredo came across Thornewood. It was transformed into a sort of modern boarding house by the Community Development Corporation of South Berkshire, a nonprofit group that develops affordable housing, and opened this year. Rent for a room with a private bathroom but tenants must share a kitchen starts at $900 a month, in a city where the average rent is $2,500, according to Zillow. Nearby, the Windflower, another inn once popular with tourists, has also been converted into worker housing and opened in 2023.

Both properties are much-needed in Berkshire County, where high housing costs and a tight market in towns like Great Barrington and Stockbridge have made finding housing difficult for workers in industries such as education and health care. The county’s apartment vacancy rate is 3.7%, up from 6.2% in 2018, and evictions have nearly doubled, according to the UMass Donahue Institute, which studies housing.

“It’s hard to buy a house on $50,000 a year, or even pay rent at this point,” said Lenox Select board member Marybeth Mitts. Ms Mitts said housing in her town had “changed dramatically since the pandemic”.

“A lot of the available housing stock started to be purchased because people were moving from Boston and New York to the lovely Berkshires,” she said.

Population growth has stabilized by 2023, but the market remains tight. The number of new building permits issued in Massachusetts has been “increasingly below the national average” since the Great Recession that began in 2007, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. The UMass Donahue Institute estimates the state will face a deficit of 222,000 housing units by 2036.

In Berkshire County, new construction has been even more anemic, said Brad Gordon, executive director of UpSide413, a nonprofit that provides housing services. Many towns have sought to preserve their rural character by adopting zoning rules requiring two- or three-acre sites for new homes, making construction expensive, he said. The lack of sewer and water services has further limited new construction.

Last year, Gov. Maura Healey signed the Affordable Housing Act, aimed at encouraging more construction. The bill allows accessory dwelling units to be on the same lot as a single-family home, allowing homeowners to build, for example, a cottage in their backyard that could be rented. State officials say more than 90,000 new housing units have been built or are under development since the law was passed.

The bill also designates resort areas, such as Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, as “seasonal communities.” Among other things, this designation allows cities to build housing specifically for workers without violating discrimination laws.

Eight towns in the Berkshires, where more than 40 percent of housing is occupied by part-time residents, also received seasonal housing designation. But towns must opt in to the program to take advantage of the provisions, and none in the Berkshires had done so as of this month. The Berkshire Eagle reported last month that only six people in the county had applied to build accessory dwelling units.

Officials from several cities, including Lenox and Stockbridge, told The New York Times they were still weighing the bill and declined to comment.

According to Mr. Gordon, some ambivalence towards the construction of affordable housing has long existed in the region. Many people say they understand the need for more housing, he said, “but if it was something that was near them or in their neighborhood, I don’t think that percentage would be as high, unfortunately.”

Efforts to build more housing have sometimes faced opposition. In 2019, for example, Lenox residents voted against a mixed-income housing project on a city-owned parcel near another new development, arguing it would strain the city’s infrastructure. A second 65-unit project, called Forge, was approved, close to a highway and further from downtown.

Patrick White, who grew up in Stockbridge and is president of the Stockbridge Affordable Housing Trust, said the housing shortage threatens to change the character of the area. Visitors have long been drawn to Stockbridge for its Gilded Age mansions, its certain Norman-Rockwell charm, and attractions like Tanglewood, the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

But Stockbridge has always had a significant year-round middle-class population – and that is changing, Mr White said.

“Nine out of 10 sales in Stockbridge are now made by seasonal residents because real estate here has become very expensive,” he said. Forty-four percent of Stockbridge homes are owned by second homes and outside investors, according to state data.

Mr. White worries that Stockbridge risks becoming another Provincetown, a Cape Cod community with a small population of full-time residents. If things don’t change, there won’t be anyone left to teach children, put out fires or serve in local government, he added.

“Everything stops working if there’s no one here from September to May,” he said.

The state’s resort housing crisis has also been exacerbated by short-term rentals. Landlords prefer to rent to vacationers during peak season rather than to year-round residents because it generates more revenue, said Edward M. Augustus Jr., the state’s Secretary of Housing and Livable Communities. (Nantucket residents voted last week to support a measure that would allow them to rent their properties without a minimum length of stay.)

“That year-round rental could have gone to a city employee or someone who works in a year-round service industry and has now lost that opportunity,” Augustus said.

Even with a slow start, Mr. Augustus said he believes many towns will eventually vote to adopt the seasonal housing designation — largely because of the growing labor shortage.

Schools in particular report having difficulty attracting teachers and other workers. “We live in a community where a beginning teacher would have a very difficult time purchasing a home or even renting year-round,” said William E. Collins, superintendent of Lenox Public Schools.

In Great Barrington, Fairview Hospital has had to recruit more and more from outside the region, said Anthony Scibelli, system vice president and chief operating officer.

“We have people coming from Connecticut and New York and from further afield in the county,” he said.

Meanwhile, some employers have had to get creative in the face of the housing crisis. Josh Irwin faced a thorny problem a few years ago while recruiting a chef for a restaurant he owns in New Marlborough in the Berkshires.

The candidate “kind of put the ball in my court: ‘You find me a place to live, because I haven’t had a chance yet,'” Mr. Irwin said.

So Mr. Irwin did something increasingly common among area business owners. He bought a small cottage on the shore of a nearby lake to house his employees. Mr. Irwin had also planned to turn Windflower into worker housing, but the plan was later carried out by Construct, a housing nonprofit.

The housing problem has become even more urgent, Mr. Irwin said. Some businesses have had to reduce their opening hours or close their doors because they could not find workers.

“It’s hard to ignore it when you go to your local coffee shop and the door is locked and there’s a sign outside the door saying, ‘Sorry, no staff.’ »