- The rivals supported by the state made the 3D open source almost impossible

- Chinese subsidies move global competition in the production of office 3D printer

- Cheap Chinese patents create obstacles far beyond the European market borders

The open source movement in 3D printing has once prospered on shared conceptions, community projects and collaboration between borders.

However, Josef Prusa, head of Prusa Research, announced: “The 3D Open Hardware Desktop printing is dead”.

The remark stands out because his business has long defended open conceptions, sharing files and innovations with the wider community.

Economic support and patent challenges

Prusa built her first cases in a small basement in Prague, packing up executives in pizzas while relying on the contributions of others who shared his philosophy.

What has changed, he argues now, is not consumer demand, but the imbalance has created when the Chinese government described 3D printing a “strategic industry” in 2020.

In his blog article, Prusa cites a study by the Rhodium group which describes how China supports its companies with subsidies, subsidies and easier credit.

This makes it much cheaper to make machines than in Europe or North America.

The problem becomes more complicated when you look at the patents. In China, the recording of a complaint costs as little as $ 125, while calling into question one varies from $ 12,000 to $ 75,000.

This gap has encouraged an increase in local deposits, often on the conceptions that return to open source projects.

The previous machines of Prusa, such as the original i3, proudly displayed partners of partners such as E3D and Noctua, embodying a community spirit, but were also easy to copy, with whole guides appearing online only a few months after the release.

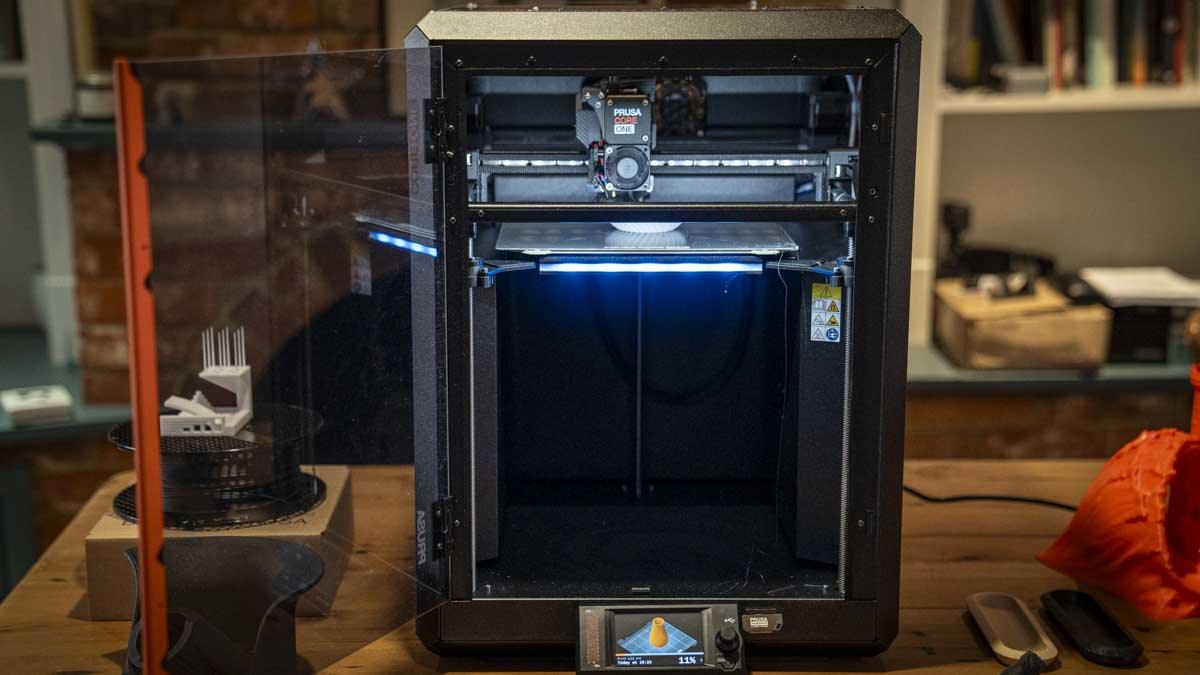

The latest Prusa printers, including MK4 and Core One, now restrict access to key electronic conceptions, even by offering STL files for printed parts.

The Nextruder system is fully owned, marking a clear retreat from the total opening.

Prusa maintains that Chinese companies actually lock the technology that the community was supposed to share – because if a patent in China does not prevent its business from selling in Europe, it prevents access to the Chinese market.

A greater risk emerges when agencies like the American patent office treat patents like “previous art”, creating expensive obstacles and which take time to erase.

Prusa cited the case of the Chinese company, Anycubic, obtaining an American patent on a multicolored center which seems similar to the MMU system that his company published for the first time in 2016.

Earlier years, Bambu Lab presented his A1 series, also inspired by the same concept.

Anycubic now sells the Kobra 3 combo with this functionality, which raises questions about how agencies grant patents and which has legitimate allegations.

Meanwhile, the Bambu laboratory faces separate legal battles with stratasys, the American pioneer whose patents have once kept 3D printing confined to costly industrial use.

Declaring the end of open equipment can be dramatic, but the pressures are real.

Between state subsidies, permissive patent rules and the increase in disputes, the basis of open collaboration is crumbling.

Via Toms equipment